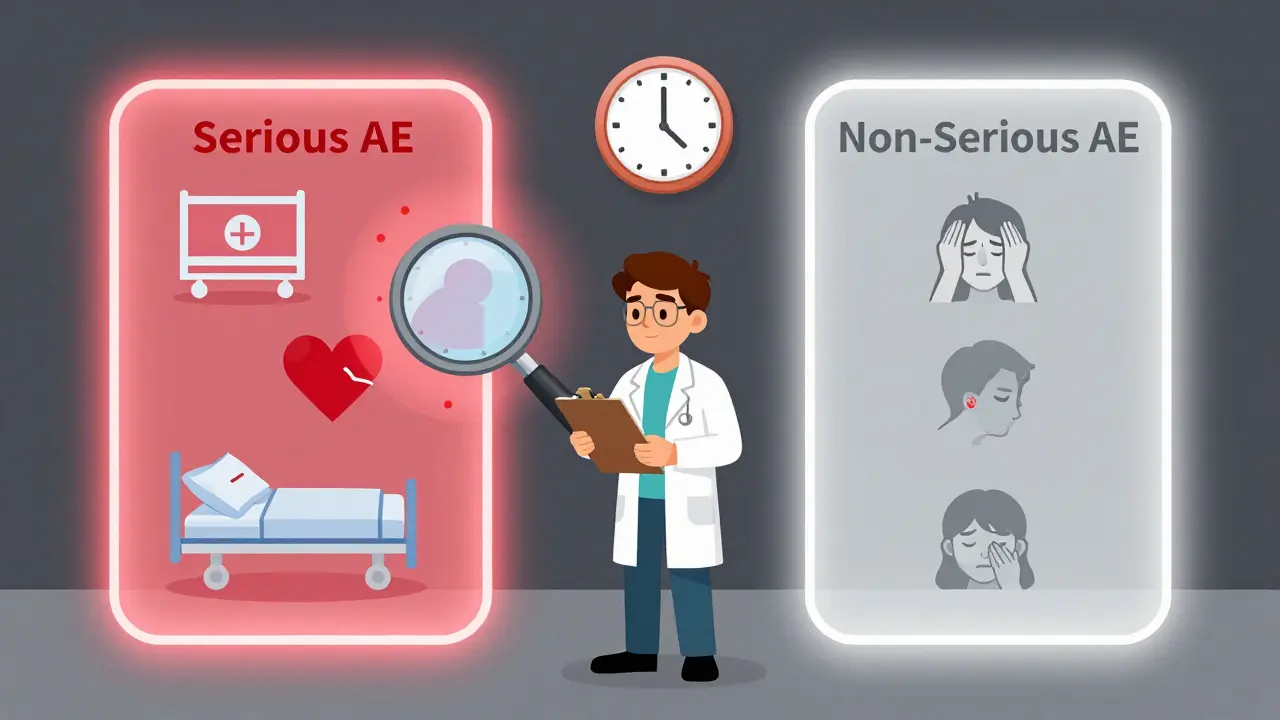

When you're running a clinical trial, every patient reaction matters-but not every reaction needs the same level of attention. The difference between a serious adverse event and a non-serious one isn’t about how bad the patient feels. It’s about what happened to them. And getting this wrong can cost time, money, and even lives.

What Makes an Adverse Event "Serious"?

An adverse event (AE) is any unwanted medical occurrence during a clinical trial, whether or not it’s linked to the drug or device being tested. But only some of these count as serious adverse events (SAEs). The definition isn’t about pain levels or how scary it looks. It’s about outcomes. According to the FDA and ICH E2A guidelines, an event is serious if it results in:- Death

- Life-threatening illness or injury

- Hospitalization (or prolonging an existing hospital stay)

- Persistent or significant disability

- Congenital anomaly or birth defect

- Any event that requires medical intervention to prevent one of the above

That’s it. No more, no less. A migraine that knocks someone out for a day? Not serious. A heart attack that sends someone to the ER? Serious-even if they’re discharged the same day. A rash that itches? Non-serious. A rash that leads to toxic epidermal necrolysis? Serious. The intensity of the symptom doesn’t matter. Only the outcome does.

Why This Distinction Matters

Confusing severity with seriousness is the #1 mistake in clinical safety reporting. A study by the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative found that nearly 37% of adverse event reports submitted to institutional review boards (IRBs) in 2019 didn’t actually meet seriousness criteria. That’s thousands of hours wasted reviewing events that don’t require urgent action.Imagine this: a researcher spends 45 minutes writing up a report for a patient who had a moderate headache. They file it as a serious event because the pain was "severe." But under the rules, a headache-even a terrible one-isn’t serious unless it leads to coma, stroke, or hospitalization. That report gets flagged, sent back, and delays the review of a real SAE that came in the same day. Now the IRB is behind. The sponsor is scrambling. The FDA’s safety system gets flooded with noise.

Dr. Janet Woodcock, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, put it bluntly in 2022: "The current system for adverse event reporting is overwhelmed by non-serious events reported as serious, diluting attention from truly critical safety signals."

When Do You Have to Report?

The clock starts ticking the moment the investigator learns about the event. For serious adverse events:- Report to the sponsor within 24 hours-no exceptions. This applies whether the event seems related to the study drug or not.

- The sponsor must report to the FDA within 7 days if the event is life-threatening, or 15 days for other serious events.

- Report to the IRB within 7 days of learning about it.

For non-serious adverse events, you don’t rush. You follow the protocol. Most studies collect these in Case Report Forms (CRFs) and report them in batches-monthly or quarterly. Some protocols don’t even require IRB reporting for non-serious events unless they’re frequent or unusual.

Here’s the catch: if a non-serious event happens repeatedly, or in a pattern, it might still become a signal worth investigating. That’s why safety monitoring boards look at trends, not just individual reports.

How to Decide: The Four-Question Test

The NIH’s 2018 guidelines offer a simple decision tree. Ask yourself:- Did the event cause death?

- Was it life-threatening? (Meaning the patient was at immediate risk of dying-this isn’t "could have died," it’s "it almost did.")

- Did it require hospitalization or extend an existing stay?

- Did it cause persistent or significant disability-or a birth defect?

If the answer is "yes" to any of these, it’s serious. If not, it’s non-serious. No guesswork. No "I think it was bad." Just facts.

For example: A patient on a new diabetes drug gets dizzy and falls, hitting their head. They go to the ER, get a CT scan, and are sent home with a mild concussion. No hospitalization. No lasting damage. That’s not serious. But if they’d been admitted for observation, or developed a brain bleed? That’s serious.

Real-World Confusion: Where People Get It Wrong

A 2022 survey of 347 research sites found that 63% had inconsistent seriousness determinations across studies. The biggest problem areas? Oncology and psychiatry.In oncology, patients often enter trials with advanced disease. A fever might be common. Is it serious? Only if it leads to sepsis, ICU admission, or death. Otherwise, it’s just part of the baseline.

In psychiatry, "severe anxiety" gets reported as serious all the time. But unless that anxiety leads to a suicide attempt, hospitalization, or self-harm requiring medical intervention, it’s not serious under regulatory definitions. Reddit threads from clinical coordinators are full of stories: "I reported a patient’s panic attack as an SAE because it was terrifying. Got it flagged as non-serious. Felt like I did something wrong." You didn’t. You just misunderstood the criteria.

Even the FDA’s own MedWatch form (Form 3500A) now includes checkboxes for each seriousness criterion to reduce errors. Training is mandatory under ICH E6(R2). Top research institutions require annual refresher courses-and 98.7% of them do.

The Cost of Getting It Wrong

This isn’t just paperwork. It’s money.The global clinical trial safety market hit $3.27 billion in 2022. Of that, over $1.89 billion went to processing adverse events-62.7% of which were misclassified as serious. That’s billions spent chasing false alarms.

At the University of California, San Francisco, 42% of AE reports in 2022 needed clarification. Each one delayed review by nearly 10 business days. The SWOG Cancer Research Network spent 18.5 full-time hours per week fixing misclassified SAEs. That’s 910 hours a year-time that could’ve gone to patient care or data analysis.

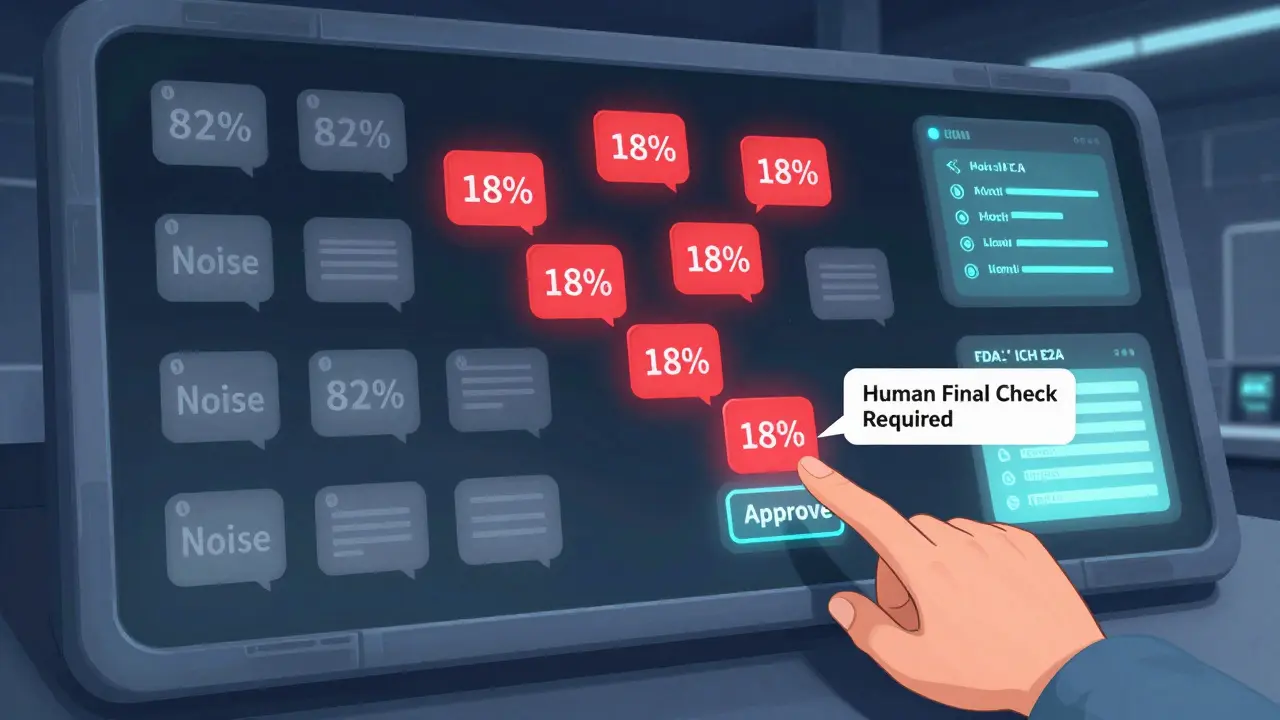

And the noise is getting worse. The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative has processed over 14.7 million adverse event reports since 2008. Only 18.3% met seriousness criteria. That means more than 8 out of 10 reports were noise.

What’s Changing? The Future of Reporting

The system is adapting. In 2023, the FDA proposed new guidance to standardize seriousness criteria across drug types. The EU’s Clinical Trials Regulation, fully in effect since early 2022, harmonized definitions across all 27 member states-cutting cross-border reporting errors by over 34%.Artificial intelligence is stepping in. Automated tools now correctly classify seriousness in 89.7% of cases, compared to 76.3% for humans. But AI still needs a human final check. No system is perfect. The goal isn’t to replace judgment-it’s to reduce error.

By 2025, the ICH’s E2B(R4) standard will roll out globally, making electronic reporting consistent across countries. The FDA’s 2024 pilot using natural language processing to auto-triage reports could cut processing time by nearly half.

What You Need to Do Today

If you’re involved in clinical research, here’s your action list:- Review the ICH E2A and FDA definitions of serious adverse events-don’t rely on memory.

- Train every new team member on the difference between severity and seriousness. Use real examples.

- Use the four-question test every time. Write it down. Stick it on your desk.

- Double-check reports before submitting. Ask: "Would this qualify if the patient wasn’t in a trial?"

- Don’t report mild symptoms as serious just because they’re common in your population.

- Use CTCAE for severity (mild/moderate/severe), but use ICH/FDA criteria for seriousness.

Getting this right isn’t about compliance. It’s about focus. When you stop reporting every cough and headache as an emergency, you free up the system to catch the real threats. That’s how you protect patients-not by over-reporting, but by reporting the right things, the right way, at the right time.

Is a severe headache a serious adverse event?

No, a severe headache is not automatically a serious adverse event. "Severe" refers to intensity, not outcome. A headache only qualifies as serious if it leads to death, life-threatening complications, hospitalization, or permanent disability. For example, a headache caused by a brain hemorrhage would be serious. A migraine that’s intense but resolves with medication is not.

Do I report non-serious adverse events to the IRB?

Usually not. Non-serious adverse events are typically documented in Case Report Forms and reported in routine summaries (monthly or quarterly). Unless your protocol specifically requires IRB reporting for mild or moderate events, they don’t need to be submitted individually. Always check your study’s Data and Safety Monitoring Plan.

What if I’m not sure whether an event is serious?

When in doubt, report it as serious and mark it as "pending determination." Then consult your safety officer or sponsor immediately. It’s better to report early and have it corrected than to miss a true SAE. Many institutions have a 24/7 safety hotline for exactly this situation.

Can a non-serious event become serious later?

Yes. If a patient initially had a moderate rash that resolved, but later develops Stevens-Johnson syndrome, the original event should be updated to reflect the new outcome. Always follow up on any event that changes in severity or outcome. Update your report immediately and notify your sponsor and IRB.

Are psychiatric events like depression or anxiety considered serious?

Only if they meet the outcome-based criteria. Severe depression or anxiety alone is not serious unless it results in suicide attempt, hospitalization, or significant functional impairment requiring medical intervention. Many researchers mistakenly report emotional distress as serious-this inflates reports and distracts from real safety signals.

What’s the difference between an adverse event and an adverse reaction?

An adverse event (AE) is any unfavorable medical occurrence during a trial, regardless of cause. An adverse reaction is an AE that has been determined to be caused by the investigational product. All adverse reactions are AEs, but not all AEs are reactions. Only adverse reactions are reported as "expected" or "unexpected" in safety summaries.

December 18, 2025 AT 15:45 PM

It’s funny how we treat medical data like it’s a legal contract. The rules are clear, but people still read into it like it’s poetry. A headache isn’t serious just because it made someone cry. That’s not medicine, that’s emotional reporting. We’re not here to validate pain-we’re here to track outcomes. Simple.

December 18, 2025 AT 16:43 PM

This is exactly why clinical trials take forever. Everyone’s scared to miss something, so they report everything. Then the system collapses under its own weight. We need discipline, not fear. Stick to the criteria. It’s not hard.

December 19, 2025 AT 06:38 AM

you ever wonder why the FDA lets big pharma control what counts as 'serious'? they dont want you to know that 80% of these 'events' are just side effects they knew about but hid for years. the whole system is rigged. they call it 'noise' but its the truth they're drowning. they dont want you to see the real pattern. watch the videos. theyre deleting them.

December 20, 2025 AT 09:31 AM

so let me get this straight youre telling me if someone has a migraine so bad they vomit and cant move for 3 days but doesnt go to the hospital its not serious? wow thats wild. so if i pass out from pain and wake up on the floor its just a bad headache? this is why people dont trust science anymore. you people are insane

December 21, 2025 AT 09:55 AM

I’ve seen this play out in three different countries. The U.S. over-reports. Europe under-reports. Asia? They just don’t report at all. But here’s the thing-none of it matters if the data isn’t clean. The four-question test is the only thing keeping us from total chaos. Use it. Teach it. Live it.

December 23, 2025 AT 08:32 AM

you think this is about patient safety? nah. its about funding. more reports = more grants. more paperwork = more jobs for people who dont actually do science. the real problem? the people who write the guidelines never ran a trial. they sit in offices in D.C. and make up rules while real clinicians burn out. this whole system is a pyramid scheme

December 25, 2025 AT 07:07 AM

you say the FDA is overwhelmed by noise but you ignore the fact that most of that noise comes from sites that dont train their staff. its not the system thats broken its the people. and before you say 'but the guidelines are confusing'-no theyre not. if you cant tell the difference between a headache and a stroke you probably shouldnt be in clinical research

December 25, 2025 AT 20:30 PM

Let me tell you something. I worked on a trial where a woman had a panic attack so bad she thought she was dying. She was 22. She’d never had one before. We didn’t report it as serious. Six months later, she tried to jump off a bridge. We didn’t see it coming. So yeah. Maybe you’re right about the rules. But what about the people behind the data? Who’s watching them? Who’s counting the silent ones?

December 27, 2025 AT 04:56 AM

One time I reported a rash as serious because the patient looked scared. Got flagged. Learned my lesson. Now I just ask: did it hospitalize them? kill them? break them? If not, it’s not serious. Simple. I keep the four questions taped to my monitor. Still works.

December 28, 2025 AT 16:37 PM

There’s a quiet horror in all of this. We’ve turned human suffering into checkboxes. We’ve made grief into a form. We’ve turned trauma into a spreadsheet. And then we wonder why people don’t trust medicine. We don’t see the person. We see the event. And when you do that long enough… you forget why you started. We’re not just reporting data. We’re burying stories. And someone’s got to remember that.