Liver Drug Dose Adjustment Calculator

How Liver Disease Affects Drug Clearance

The liver processes most medications through enzymes and blood flow. In cirrhosis, blood flow drops to 0.8-1.0 L/min (vs 1.5 L/min healthy), enzymes decrease by 30-60%, and transporters reduce by 50-70%. This causes dangerous drug accumulation.

Results

Enter your dose and drug type to see safe adjustment

When your liver is damaged, it doesn't just affect how you feel-it changes how your body handles every pill you take. For millions of people with chronic liver disease, standard drug doses can become dangerous. The liver doesn't just process alcohol or toxins; it's the main factory for breaking down most medications. When it's impaired, drugs don't clear the way they should. That means they build up. And that buildup can lead to overdose-even when you're taking the exact dose your doctor prescribed.

Why the Liver Matters for Every Drug You Take

The liver doesn't just filter blood. It transforms drugs into forms your body can use or get rid of. Most medications are processed by enzymes like CYP3A4 and CYP2E1, which break them down so they can be excreted. But in liver disease, these enzymes don't work as well. In advanced cirrhosis, CYP3A4 activity drops by 30-50%, and CYP2E1 falls by 40-60%. That means drugs like opioids, benzodiazepines, and many antibiotics stick around much longer than they should.It's not just enzymes. The liver also uses transport proteins like OATP1B1 to pull drugs into liver cells for processing. In cirrhosis, these transporters drop by 50-70%. So even if the enzymes were working fine, many drugs can't even get inside the liver to be broken down.

And then there's blood flow. In a healthy liver, about 1.5 liters of blood pass through every minute. In cirrhosis, that drops to 0.8-1.0 liters. Worse, up to 40% of that blood bypasses the liver entirely through abnormal shunts. That means oral drugs-like painkillers or sedatives-skip the first-pass metabolism they normally undergo. They hit your bloodstream stronger and faster than expected.

High-Extraction vs. Low-Extraction Drugs: What’s the Difference?

Not all drugs are affected the same way. The key is whether they're high- or low-extraction drugs.High-extraction drugs (extraction ratio >0.7) rely mostly on liver blood flow. Examples: fentanyl, morphine, propranolol. If blood flow drops, clearance drops. In cirrhosis, these drugs can accumulate quickly. Dose reductions of 50-75% are often needed in severe cases.

Low-extraction drugs (extraction ratio <0.3) depend on enzyme activity, not blood flow. These make up about 70% of commonly prescribed drugs. Examples: diazepam, lorazepam, methadone, warfarin. Even small drops in enzyme function can cause big changes in how long these drugs last. For instance, warfarin clearance falls by 30-50% in cirrhosis. A standard 5 mg dose can push INR levels dangerously high, increasing bleeding risk.

Here’s the catch: you can’t tell just by looking at liver tests. A patient with high bilirubin and low albumin might have the same enzyme activity as someone with normal labs but advanced fibrosis. That’s why blanket rules don’t work.

Child-Pugh and MELD: The Real Tools for Dosing

Doctors used to guess. Now, they use objective scores.The Child-Pugh-Turcotte score looks at five things: bilirubin, albumin, INR, ascites, and encephalopathy. It classifies liver disease into Class A (mild), B (moderate), or C (severe). The FDA and EASL recommend using this to guide dosing. For example:

- Child-Pugh A: Usually no adjustment needed for low-extraction drugs

- Child-Pugh B: Reduce dose by 25-50% for most hepatically cleared drugs

- Child-Pugh C: Reduce dose by 50-75% or avoid entirely

The MELD score (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) is even more precise. It uses bilirubin, INR, and creatinine to predict survival. Every 5-point increase above MELD 10 reduces drug clearance by about 15%. That’s why some hospitals now use MELD to fine-tune doses for drugs like opioids or antivirals.

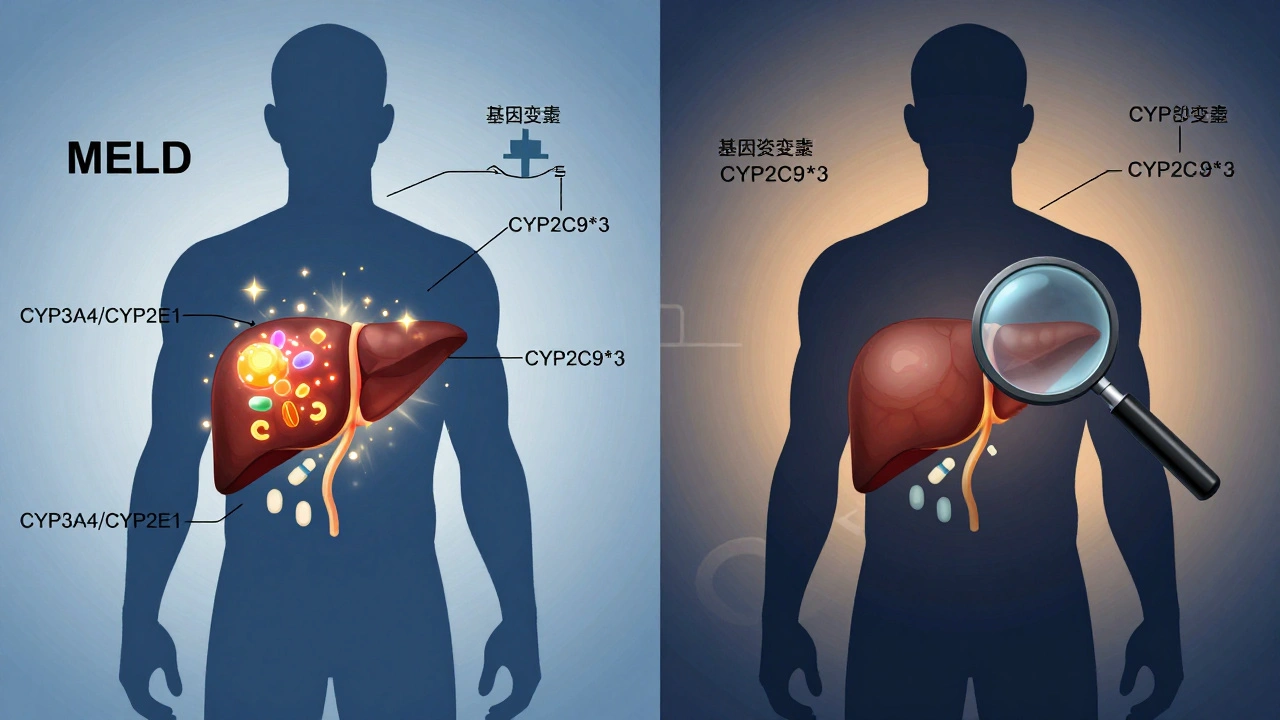

But here’s what most clinicians still miss: these scores don’t tell you about enzyme activity. Two patients with identical MELD scores can have wildly different CYP3A4 function. That’s why therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) is critical for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows-like warfarin, tacrolimus, or phenytoin.

Real-World Drug Examples: What to Watch For

Some drugs are safe. Others are landmines.

Warfarin: Clearance drops 30-50%. Dose reductions of 25-40% are common. INR must be checked weekly at first. A standard 5 mg dose can cause serious bleeding in cirrhotic patients.

Benzodiazepines: Diazepam has active metabolites that build up. In cirrhosis, use only 30-50% of the normal dose. Lorazepam? Better choice. It’s metabolized by glucuronidation, not CYP enzymes, and doesn’t produce active metabolites. Dose reduction is still needed-just less (25-40%).

Opioids: Morphine and fentanyl are high-extraction. Dose reductions of 50% or more are needed. But here’s the twist: even when levels are normal, the brain is more sensitive. A dose that’s safe in a healthy person can cause coma in someone with cirrhosis. Hepatic encephalopathy can be triggered by just one extra pill.

Antibiotics: Ceftriaxone is mostly renally cleared, but studies show peak levels jump 40-60% in cirrhosis. That’s because protein binding drops-more free drug circulates. The same goes for metronidazole and clarithromycin.

Sugammadex: This reversal agent for muscle relaxants is 96% excreted by the kidneys. No dose adjustment needed. But recovery time? Slower-by 40%. That’s not about metabolism; it’s about reduced muscle function and delayed elimination.

What About New Drugs? Are They Safer?

Yes-and no.

In 2023, the FDA approved 18 new drugs with specific dosing instructions for liver impairment-a 25% jump from 2022. Drug companies now have to test new medications in patients with mild, moderate, and severe liver disease. That’s thanks to EMA’s 2022 mandate and FDA’s 2023 guidance.

But here’s the problem: most of these studies still use Child-Pugh categories. They don’t account for individual enzyme variation. A patient with a CYP2C9*3 allele (found in 8.3% of Caucasians) will metabolize warfarin even slower than someone with the same MELD score but normal genetics.

That’s why the future is moving toward physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling. These computer models simulate how a drug moves through a virtual liver with specific blood flow, enzyme levels, and shunting. Studies show they predict drug exposure with 85-90% accuracy. By 2030, experts predict most drug labels will include model-based dosing-not just Child-Pugh categories.

Why Standard Dosing Fails-And What Works Instead

Most hospitals still use one-size-fits-all dosing. That’s why the TARGET-HepC study found 22.7% of patients with Child-Pugh C cirrhosis failed antiviral treatment-because their doses weren’t adjusted.

But when pharmacists use personalized approaches-checking MELD, enzyme activity, drug levels, and genetics-adverse events drop by 34.2%. That’s not a small win. It’s life-saving.

Here’s what works in practice:

- Always check the drug’s hepatic metabolism pathway before prescribing.

- Use MELD or Child-Pugh to estimate severity-not just ALT or AST.

- For high-risk drugs (opioids, warfarin, antiepileptics), use therapeutic drug monitoring.

- Start low, go slow. Double-check doses with a pharmacist.

- When in doubt, avoid the drug. Use alternatives with renal clearance (like lorazepam instead of diazepam).

And remember: liver disease doesn’t make people more likely to have bad reactions. But it makes them less able to recover from them. A drug that causes mild drowsiness in a healthy person can cause coma in someone with cirrhosis. That’s not an allergy. That’s pharmacokinetics.

What’s Next? The Future of Liver-Based Dosing

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)-formerly fatty liver-now affects 30% of U.S. adults. Even early-stage MASLD reduces CYP3A4 activity by 15-25%. That means people with obesity and diabetes, who aren’t yet cirrhotic, may still need lower doses of common drugs.

Pharmacists are stepping up. Between 2020 and 2023, pharmacist-led dose adjustment services for liver patients increased 40%. The market for therapeutic drug monitoring in liver disease is projected to hit $1.24 billion by 2026.

The message is clear: liver disease isn’t just a liver problem. It’s a medication problem. And treating it like one saves lives.

December 2, 2025 AT 21:55 PM

Man, I never thought about how my liver was basically the bouncer for every pill I took. I’ve been on painkillers for years after that back injury, and now that I’ve got fatty liver, my doc just said ‘take less’-but never explained why. This post broke it down like I’m five. Thanks.

Turns out my body’s not broken, it’s just been lied to by pharma ads.

December 4, 2025 AT 11:21 AM

Oh wow, so the liver’s just a lazy intern who forgot to clock in? CYP3A4 down 50%? OATP1B1 in the dumpster? And blood flow’s doing the ‘I’m outta here’ shuffle through shunts? This isn’t medicine, this is a Shakespearean tragedy starring your hepatocytes.

Also, who approved the word ‘extraction ratio’? Sounds like a porn site for chemists.

December 5, 2025 AT 18:59 PM

Really appreciate this breakdown 🙏. The enzyme + transporter + blood flow triad is everything. I work in pharmacokinetics and this is exactly why we have ‘hepatic impairment’ dosing guidelines-though most prescribers still ignore them.

Pro tip: If you’re on a drug with >0.7 extraction ratio and have cirrhosis, assume it’s 3x more potent. Always start low. Go slow. Your liver’s not mad, it’s just exhausted.

December 5, 2025 AT 23:47 PM

It’s fascinating how the pharmaceutical industry has systematically ignored hepatic pharmacokinetics in favor of profit-driven dosing algorithms. The CYP450 system is not some mystical black box-it’s a finely tuned metabolic orchestra, and we’ve been playing it with a kazoo.

Meanwhile, the FDA still approves drugs without mandatory hepatic impairment trials. Absurd. This is not science. This is negligence dressed in white coats.

December 7, 2025 AT 10:34 AM

They’re hiding this. They HAVE to be. Why else would they let people with cirrhosis get prescribed Xanax? Or opioids? This is genocide by prescription. I know a woman who died from a ‘normal’ dose of tramadol. Her liver was failing for YEARS. Nobody told her. Nobody warned her. It’s all corporate greed.

And don’t even get me started on Big Pharma’s lobbying. They’re poisoning us-and calling it ‘treatment’.

December 7, 2025 AT 23:04 PM

Bro this is all a scam. Liver doesn’t process drugs. The government uses the liver as a scapegoat so they can sell you ‘special’ meds for extra cash. Real doctors know: it’s the gut bacteria that metabolize everything. The liver? Just a myth. I read it on a forum in 2017. Still true.

Also, glyphosate ruins your enzymes. That’s why.

December 9, 2025 AT 01:27 AM

This is why African and Indian populations have higher drug toxicity rates-our livers are already under siege from malaria, hepatitis B, malnutrition, and contaminated water. Western medicine treats the liver like a machine that breaks when you push it. But in our reality, it’s been fighting a war since birth.

We don’t need ‘dose adjustments.’ We need healthcare equity. And clean water. And fewer pills that don’t work anyway.

December 10, 2025 AT 23:41 PM

Bro I had cirrhosis from drinking too much beer (RIP 2018-2020). My doc told me to cut back on ibuprofen. I didn’t know why. Now I get it. My liver was basically a burnt-out toaster. This post made me cry a little. Thanks for the clarity. 🙏

Also, if you’re reading this and still popping NSAIDs like candy? Stop. Your liver doesn’t owe you pain relief.

December 11, 2025 AT 21:06 PM

As a nurse who’s seen patients overdose on ‘normal’ doses, this is SO important. I once had a 72-year-old woman on a low-dose benzo for anxiety-her liver was failing, and she was nodding off at breakfast. We had to switch her to non-metabolized meds. No one told her the dose was dangerous.

Doctors need to be better educated. Patients need better warnings. And pharmacies? They need to flag high-risk meds automatically. This isn’t just science-it’s safety.

December 12, 2025 AT 21:12 PM

Wow, you actually believe all this CYP3A4 nonsense? I’ve read the original papers-most of these studies are done on rats with surgically removed livers. Real human livers adapt. The body compensates. You’re overestimating enzyme activity loss by 200%.

Also, why are you ignoring the role of gut microbiota? That’s where 60% of drug metabolism happens now. This post is outdated. Like, 2010 outdated.

December 12, 2025 AT 23:03 PM

Bro, you’re right about the gut microbiome-it’s huge. But that doesn’t erase the 50% drop in CYP3A4 in cirrhosis. The studies are from human liver biopsies, not rats. And the gut can’t compensate for blood shunting or transporter failure. You’re cherry-picking.

Also, if you’re gonna call it ‘2010 outdated,’ at least cite the 2023 AASLD guidelines that reaffirmed these exact principles. Just saying.