When a generic drug hits the shelf, you might assume it’s just a cheaper copy of the brand-name version. But behind that simple label is a rigorous science battle-testing whether the generic actually performs the same way in the body. This is where bioequivalence testing comes in. Two main methods are used: in vivo (inside the body) and in vitro (outside the body). Each has its place, and choosing the wrong one can delay approval, cost millions, or even risk patient safety.

What Bioequivalence Really Means

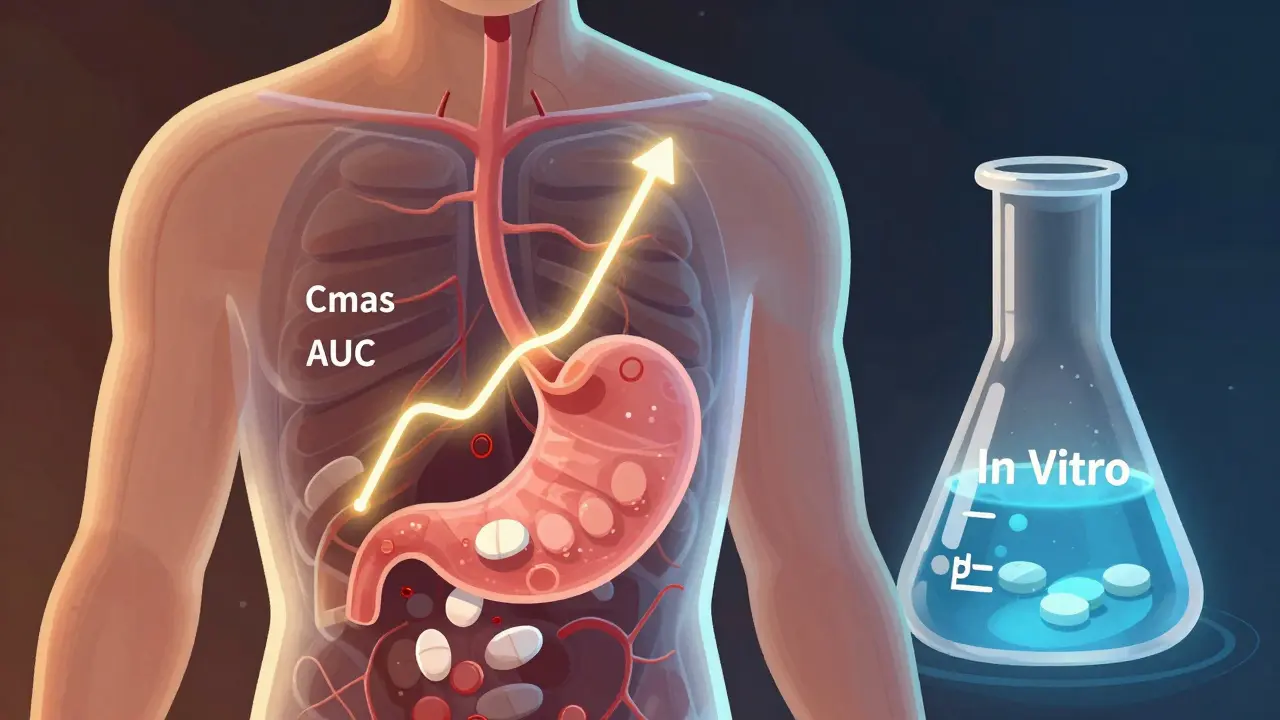

Bioequivalence isn’t about matching ingredients-it’s about matching performance. The FDA requires that a generic drug delivers the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate as the original. That’s measured by two key numbers: Cmax (peak concentration) and AUC (total exposure over time). For most drugs, the generic’s values must fall between 80% and 125% of the brand-name drug’s. For drugs with narrow therapeutic windows-like warfarin or levothyroxine-that range tightens to 90%-111%. If the numbers don’t line up, the drug won’t be approved.In Vivo Testing: The Gold Standard

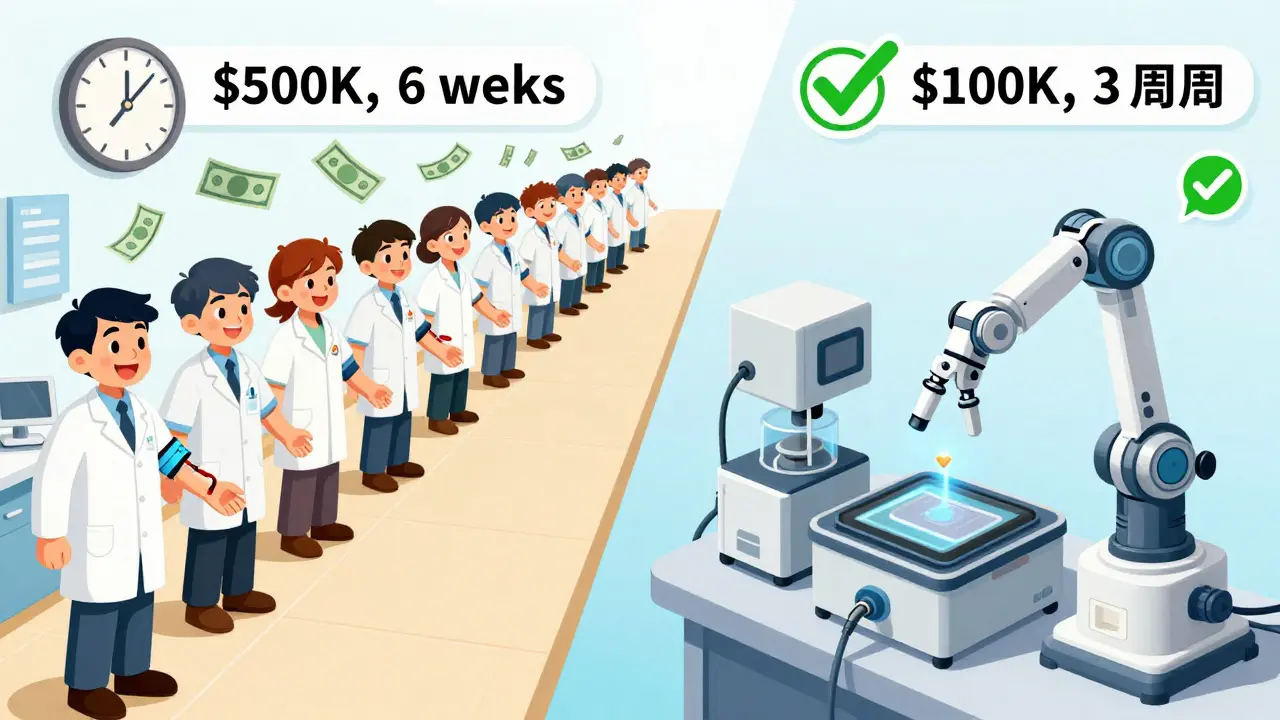

In vivo testing means testing on humans. It’s the traditional, most trusted method. Healthy volunteers take the generic and brand-name drugs in a crossover study-sometimes fasting, sometimes after a meal-then have their blood drawn over hours to track how the drug moves through their system. A typical study involves 24 people, lasts 4-6 weeks, and costs between $500,000 and $1 million. Why use it? Because it’s the only way to see how the body actually responds. It captures everything: stomach pH, gut motility, enzyme activity, food effects, and even individual metabolism differences. If a drug is absorbed differently when taken with food, you need in vivo testing to find out. It’s mandatory for drugs with:- Narrow therapeutic index (small difference between effective and toxic dose)

- Nonlinear pharmacokinetics (dose changes don’t predict blood levels linearly)

- Complex release profiles (extended-release tablets, patches, or implants)

- Unknown or unpredictable absorption patterns

In Vitro Testing: The Smart Alternative

In vitro testing skips the humans and goes straight to the lab. It measures physical and chemical properties: how fast the tablet dissolves, how small the particles are, how evenly the drug is distributed in an inhaler. Think of it as stress-testing the product under controlled conditions. The most common method is dissolution testing. For immediate-release tablets, you test the drug’s release in fluids mimicking stomach pH (1.2), small intestine (6.8), and sometimes with surfactants. If 90% of the drug dissolves within 30 minutes under multiple conditions, regulators often accept that as proof of bioequivalence-especially for BCS Class I drugs (high solubility, high permeability). In vitro methods are faster, cheaper, and more repeatable. A single dissolution test might cost $50,000-$150,000 and take 2-4 weeks. Coefficient of variation (CV) is often below 5%, compared to 10-20% in human studies. That’s why the FDA now accepts in vitro testing for:- BCS Class I drugs (78% of biowaivers in 2021 were for these)

- Topical creams and ointments where absorption isn’t systemic

- Inhalers and nasal sprays (where human testing is ethically and logistically hard)

- Products with validated IVIVC (in vitro-in vivo correlation)

When In Vitro Fails

In vitro isn’t magic. It doesn’t replicate the human body. A drug might dissolve perfectly in a lab beaker but get trapped in stomach mucus or broken down by enzymes before absorption. That’s why in vitro testing fails for:- BCS Class III drugs (high solubility, low permeability)-only 65% accuracy in predicting in vivo performance

- Drugs with absorption windows (only absorbed in specific gut sections)

- Products with complex excipients that change how the drug behaves in real guts

The Hybrid Future

The future isn’t in vivo or in vitro-it’s both, plus modeling. The FDA is pushing for model-informed bioequivalence. That means using computer simulations (PBPK models) to predict how a drug will behave based on in vitro data. In 2023, the FDA approved a modified-release drug using PBPK modeling instead of human trials. Regulators are also developing more realistic in vitro setups: flow-through cells that mimic gut movement, artificial membranes that replicate intestinal walls, and dissolution media that change pH like a real digestive tract. The goal? To replace 80% of in vivo studies with smarter in vitro and modeling approaches by 2030. But for now, if you’re making a generic version of a narrow-therapeutic-index drug, don’t skip the human study. The cost of failure isn’t just money-it’s patient safety.

Choosing the Right Path

Here’s how to decide:- Is it a BCS Class I drug? (High solubility, high permeability-like atorvastatin or metoprolol) → In vitro is likely enough.

- Is it a topical, inhaled, or nasal product? → In vitro is preferred, often required.

- Is it a modified-release tablet or patch? → You need IVIVC data. If you don’t have it, prepare for in vivo.

- Is it a narrow-therapeutic-index drug? → In vivo is non-negotiable.

- Does food affect absorption? → You’ll need both fasting and fed-state in vivo studies.

What’s Next

By December 2025, the FDA plans to release two new guidances on in vitro testing for complex products like nasal sprays and injectables. The European Medicines Agency has already approved 214 biowaivers based on in vitro data in 2022-a 27% jump from 2020. Japan and the EU now follow the same standards as the U.S. for BCS Class I drugs. The message is clear: in vitro testing isn’t the future-it’s already here. But it’s not a shortcut. It’s a science. And it only works when you understand the drug’s behavior inside the body-even if you’re not testing inside it.Can in vitro testing replace all in vivo bioequivalence studies?

No. In vitro testing works well for simple, high-solubility drugs (BCS Class I) and locally acting products like inhalers or creams. But for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows, complex release profiles, or food-dependent absorption, in vivo studies are still required. The FDA won’t approve a generic version of warfarin or levothyroxine based on dissolution tests alone.

Why is in vitro testing cheaper than in vivo?

In vitro testing avoids the high costs of recruiting and managing human volunteers, clinical site fees, blood draws, lab analysis for pharmacokinetics, and regulatory documentation for human trials. An in vitro study typically costs $50,000-$150,000 and takes weeks. An in vivo study can cost $500,000-$1 million and take 3-6 months.

What is IVIVC and why does it matter?

IVIVC stands for in vitro-in vivo correlation. It’s a mathematical model that links lab dissolution data to actual human absorption. If you have a strong IVIVC (r² > 0.95), regulators accept in vitro results as proof of bioequivalence. This is critical for extended-release products where human testing is expensive and time-consuming.

Are there any drugs that can’t be tested in vitro at all?

Yes. Drugs with nonlinear pharmacokinetics, low permeability (BCS Class III), or those that rely on gut enzymes or transporters for absorption often can’t be reliably predicted by in vitro methods. The FDA still requires in vivo studies for these. Also, any drug with a narrow therapeutic index-where even small differences in absorption can cause harm-must be tested in humans.

How long does it take to develop a valid in vitro bioequivalence method?

It typically takes 4 to 12 weeks, depending on complexity. For a simple tablet, it might be 4 weeks. For a nasal spray with multiple particle sizes and actuation patterns, it can take 6-12 months to validate the method to FDA standards. You also need specialized equipment like USP Apparatus 4 flow-through cells, which cost $85,000-$120,000.

What’s the role of the FDA in approving in vitro methods?

The FDA sets the standards. They publish guidances on acceptable dissolution methods, particle size ranges, and IVIVC requirements. They also review submissions and may request additional data. Their 2023 draft guidance explicitly allows in vitro-only approval for certain nasal and inhalation products, signaling a shift toward science-based, not just tradition-based, regulation.

December 22, 2025 AT 15:49 PM

So let me get this straight-we spend a million bucks to watch 24 people swallow pills and pee in cups, but we can simulate it in a beaker for 50K? And the FDA’s okay with this? I mean, I get it, but also… we’re basically trusting a robot to mimic a human gut. That’s either genius or a disaster waiting to happen. I’m betting on both.

Also, someone please tell me why we still call it ‘bioequivalence’ when it’s really just ‘blood level matching.’ We’re not testing if the pill makes you feel better-we’re testing if your bloodstream agrees with the math. Kinda sad, really.

December 22, 2025 AT 17:45 PM

The dissolution profile of BCS Class I compounds exhibits statistically significant correlation with pharmacokinetic parameters under fasting conditions, as validated by the 2021 FDA guidance on biowaivers. The coefficient of variation in vitro is consistently below 5%, whereas in vivo inter-subject variability exceeds 15% due to gastrointestinal heterogeneity. Consequently, the reliance on human trials for low-risk formulations constitutes an inefficient allocation of regulatory resources.

December 23, 2025 AT 02:58 AM

Of course the FDA loves in vitro. It’s cheaper. It’s faster. It’s less messy. But let’s not pretend this isn’t corporate cost-cutting dressed up as ‘science.’ You think they’d approve a generic insulin based on a dissolution test? No. But they’ll let you sell a generic nasal spray with zero human data? Absolutely. Because no one’s gonna die from a bad nasal spray… right?

Wait. Actually, people have. And they’re still selling it. So yeah. Science.

December 24, 2025 AT 11:10 AM

For anyone new to this topic, think of it like baking. In vitro is testing the flour, sugar, and oven temperature. In vivo is actually baking the cake and seeing if it rises, smells right, and doesn’t give your cousin food poisoning.

For simple recipes (like a vanilla cake), you can predict the outcome pretty well from the ingredients. But if you’re making a soufflé or a gluten-free chocolate lava cake? You gotta bake it. No shortcuts. And if you skip the bake? Someone’s gonna be disappointed-or worse.

December 24, 2025 AT 17:44 PM

Bro this whole system is rigged. Big Pharma don’t want no human trials because they too lazy to pay people. So they got the FDA to say ‘oh yeah, just dissolve it in water and call it good.’ But then when people get sick from generics? Oh no, that’s not our fault, we followed the rules!

And now they wanna replace ALL human testing with robots? Bro, my phone glitches when I text my mom. You really trust a machine to know how my stomach feels after a burrito?

December 25, 2025 AT 08:52 AM

Interesting how the same people who scream ‘trust the science’ when it’s vaccines suddenly get suspicious when it’s generic drugs. In vitro isn’t a loophole-it’s a refinement. The science is just… better now. We’ve had 30 years of data to build these models. We’re not guessing anymore. We’re calculating.

Also, if you’re on warfarin? Yeah, stick with in vivo. But if you’re taking ibuprofen? Chill. Your body’s not gonna turn into a science experiment.

December 26, 2025 AT 23:24 PM

Our nation spends billions on drug testing while our roads crumble. This is why America is falling behind. We prioritize corporate convenience over national infrastructure. The FDA is not a regulatory body anymore. It is a corporate liaison. This is not science. This is surrender.

And we wonder why people don’t trust medicine.

December 28, 2025 AT 08:08 AM

They’re using AI models to replace human trials? That’s the same tech that thinks a cat is a toaster. You really think a computer can model how your liver metabolizes a drug after you ate a greasy pizza and drank three energy drinks? No. This is all part of the Great Drug Replacement Agenda. The real drug is still in your system. They just don’t want you to know.

Also, the FDA is owned by Pfizer. You think that’s a coincidence?

December 29, 2025 AT 00:04 AM

Oh I just love how this whole field is quietly evolving into something so elegant. Remember when we thought you needed a whole clinical trial just to prove a pill worked? Now we’ve got dissolution curves that predict absorption like a weather forecast for your bloodstream. It’s like we’ve gone from using a hammer to build a house to using a 3D printer.

And the best part? The regulators are actually listening. They’re not just clinging to tradition-they’re adapting. I mean, look at Teva’s nasal spray approval. That’s not just innovation. That’s *progress*. It’s quiet, it’s nerdy, it’s not sexy-but it’s saving lives and money. And honestly? That’s the kind of heroism we don’t celebrate enough.

Also, the idea of artificial gut lining that mimics pH shifts? That’s science fiction becoming science fact. I’m not crying. You’re crying.

December 29, 2025 AT 15:09 PM

Let’s be real-this isn’t about cutting corners. It’s about cutting *waste*. Why test 24 people when you can test 1000 tablets in a day? Why spend $1M when you can spend $100K and get better data? This isn’t laziness. This is evolution.

And if you think in vitro is ‘not real’-go ask a pharmacist who’s watched generics fail because of inconsistent dissolution. The lab doesn’t lie. The human body? Sometimes it’s just… noisy.

Also, PBPK models? That’s the future. We’re not replacing humans-we’re augmenting them. And honestly? That’s the most American thing we’ve done in years.

December 30, 2025 AT 17:09 PM

Biggest takeaway? In vitro isn’t the opposite of in vivo-it’s the *partner*. It’s the first checkpoint. The filter. The smart pre-screen.

Think of it like a job interview. You don’t bring 500 people in for a full day of work tests. You screen resumes, run skills assessments, maybe a 30-minute task. Only the top 5% go to the final round. That’s in vitro. The final round? In vivo.

And yeah, for warfarin? You still need the final round. But for ibuprofen? Let’s save the humans for the hard stuff.

Also, if you’re a student reading this? This is why you study pharmacokinetics. This is where science gets real. And it’s beautiful. 💪🧠