Why your medicine might not be on the shelf

It’s November 2025, and a cancer patient in Sydney waits for a life-saving drug that’s been out of stock for six weeks. Not because it’s rare. Not because demand spiked. But because the active ingredient was made in a factory in Shanghai, and a port strike in Ningbo shut down shipments for 47 days. That’s not an anomaly-it’s the new normal.

More than 80% of the active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) used in medicines sold in the U.S., Australia, and the EU come from just two countries: China and India. This isn’t a flaw in the system. It was designed this way. For decades, drugmakers chased the lowest cost, and Asia delivered. But now, that efficiency is breaking down-and the cost isn’t just financial. It’s human.

The hidden cost of cheap drugs

Back in 2010, a single tablet of metformin, used by millions with type 2 diabetes, cost less than 1 cent to produce in China. Today, it’s still around 1.2 cents. But here’s what you don’t see: the 18-month lead time to get that tablet from factory to pharmacy. The 50% longer shipping delays from China to the U.S. since 2019. The 75% of pharmaceutical companies that say tariffs have raised their input costs.

When a factory in India shuts down for an environmental inspection, or a Chinese port closes due to labor unrest, it doesn’t just delay a shipment. It triggers a chain reaction. The drug manufacturer in Germany can’t fill orders. The distributor in Australia runs out. Pharmacies ration. Patients skip doses. Hospitals switch to more expensive alternatives-or worse, offer nothing at all.

In 2024, over 120 drug shortages were reported in Australia alone. Half of them were linked to raw material delays from overseas. That’s not a glitch. It’s structural.

How did we get here?

It started with globalization. After the WTO formalized trade rules in 1995, pharmaceutical companies began outsourcing everything they could. APIs, packaging, even final assembly moved to countries with lower labor costs and looser regulations. By 2020, 40% of global API production was concentrated in just three Chinese provinces. India, meanwhile, became the world’s pharmacy for finished generic drugs.

The logic was simple: save money, scale up, and rely on global logistics to deliver. But that system assumed stability. It didn’t account for pandemics, trade wars, or climate disruptions. When the pandemic hit, China locked down. India banned API exports to protect its own supply. Suddenly, the world’s drug supply chain looked less like a network and more like a single wire.

By 2023, the U.S. government flagged 26 critical drugs as vulnerable to supply shocks. By 2025, that number had jumped to 41. Many of these are antibiotics, heart medications, and cancer treatments. Not luxury items. Life-or-death essentials.

What’s being done-and why it’s not enough

Companies are waking up. In 2025, 78% of pharmaceutical firms are using inventory buffers, dual sourcing, or regional suppliers. That’s up from just 35% in 2020. Some are moving production closer to home. A major U.S. generic drugmaker shifted its insulin production from Hyderabad to Monterrey, Mexico. Lead times dropped from 60 days to 18. Costs rose 15%, but reliability jumped from 82% to 98% on-time delivery.

Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) has started fast-tracking approvals for local API production. Two new manufacturing plants opened in Victoria in 2024, backed by federal grants. One now produces metformin and metoprolol-two of the most commonly prescribed drugs in the country.

But scaling local production is slow. Building a GMP-certified API plant takes 3-5 years and costs at least $200 million. That’s why most companies are still playing it safe: they keep their main supplier in China, but add a backup in Vietnam or Poland. It’s not reshoring. It’s multi-shoring.

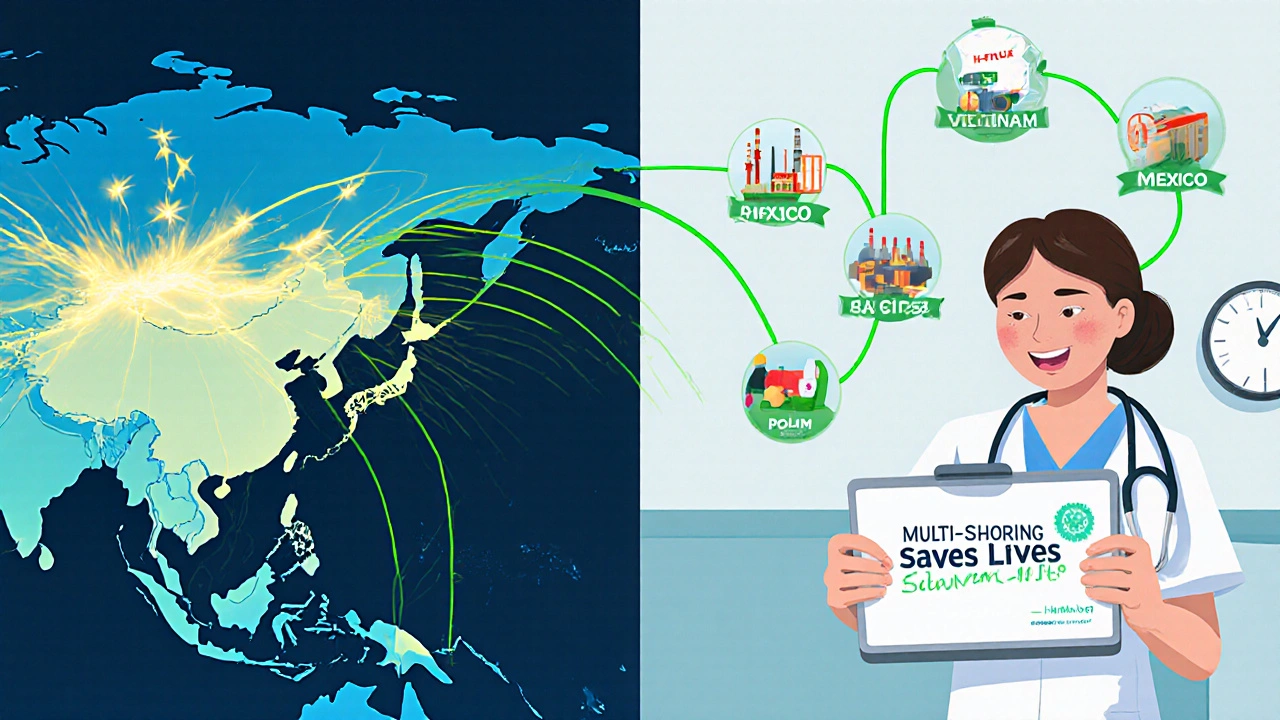

The rise of multi-shoring: a smarter way forward

Multi-shoring isn’t about bringing everything home. It’s about spreading risk. Instead of relying on one factory in one country, companies now use three or four across different regions. One makes the API. Another does the tablet pressing. A third handles packaging.

This isn’t theoretical. A Fortune 500 medical device maker in the U.S. switched from single-source Chinese suppliers to a three-country model: China for bulk chemicals, Poland for sterile filling, and Mexico for final assembly. When the Yangtze River flooded in late 2024, shutting down the Chinese plant, the rest of the chain kept running. They lost zero days of production.

And it’s working. Companies using multi-shoring report 65% fewer disruption days per year. Their inventory costs are up 15%, but their ability to deliver on time is up 22%. For drugs, that’s not just a business win-it’s a health win.

Why nearshoring to Mexico and Southeast Asia is the real game-changer

Let’s talk about Mexico. It’s not perfect. Labor costs there are 20% higher than in China. But it’s 30-40% cheaper to ship goods from Monterrey to Los Angeles than from Shanghai to Seattle. Customs clearance takes 48 hours instead of 10 days. Time is the new currency in pharma.

Same with Vietnam. It’s not China. But it’s got the skilled workers, the infrastructure, and the willingness to play by international rules. In 2024, Vietnam’s pharmaceutical exports to the U.S. jumped 47%. India is still a powerhouse-but now, it’s being joined by Indonesia, Malaysia, and even the Czech Republic.

The goal isn’t to replace Asia. It’s to reduce overdependence. Right now, if you need a drug and your only supplier is in one place, you’re gambling with your health. Multi-shoring turns that gamble into a safety net.

The invisible threat: cybersecurity and workforce gaps

It’s not just about geography. It’s about technology. Modern supply chains run on digital twins, AI forecasting, and blockchain tracking. But 60% of manufacturers say they’re worried about cyberattacks on their logistics systems. One ransomware attack on a European API supplier in 2024 delayed shipments for three months.

And there aren’t enough people to run these systems. In 2025, 33% of pharmaceutical companies report critical staffing shortages in global trade and compliance roles. The people who know how to navigate export controls, customs codes, and FDA regulations are in short supply. Training them takes years. Hiring them costs more.

That’s why companies are investing in AI tools that predict delays before they happen. One Australian firm now uses machine learning to monitor port congestion, weather patterns, and political unrest in real time. It doesn’t stop a strike. But it gives them a 14-day heads-up to reroute shipments.

What this means for you

If you take medication regularly, you’re already feeling the effects of this broken system. Maybe your prescription was switched to a different brand. Maybe you had to wait weeks for a refill. Maybe your doctor told you to take a less effective alternative.

These aren’t isolated incidents. They’re symptoms of a global system that prioritized cost over resilience. And the truth is, we can’t go back to the old way. Even if we wanted to, it’s not economically feasible. U.S. manufacturing wages are 4.8 times higher than China’s. We can’t out-cost Asia.

But we can out-smart it. By diversifying suppliers. By investing in regional production. By demanding transparency from manufacturers. By supporting policies that fund local API production-not just as a patriotic gesture, but as public health infrastructure.

What’s next? The path to resilience

The OECD forecasts global GDP growth will dip to 2.9% in 2025, partly because of trade barriers. But if countries work together-expanding trade with India, strengthening partnerships with Mexico, and creating joint stockpiles of critical drugs-we could see that number climb back to 3.1% by 2027.

Here’s what needs to happen:

- Government incentives for local API production. Australia’s $1.2 billion National Medicines Strategy is a start. More countries need similar plans.

- Standardized global regulations. Right now, a drug approved in the U.S. might take 18 months to get cleared in Australia. Harmonizing approvals saves time and lives.

- Strategic stockpiles. Not just for pandemics. For everyday shortages too. The U.S. has a Strategic National Stockpile. It’s time Australia and the EU had one for essential medicines.

- Transparency. Patients should know where their drugs are made. Not just on the box-but in public databases. If you’re on a drug that relies on a single factory in China, you deserve to know the risk.

The future of medicine isn’t about making everything at home. It’s about making sure it can be made, anywhere, if one source fails. That’s not just good business. It’s basic healthcare.

Why are so many drugs made in China and India?

China and India dominate pharmaceutical production because they offer low labor costs, strong chemical manufacturing infrastructure, and decades of experience in producing active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) at scale. By 2025, over 80% of APIs used in Western medicines come from these two countries. This wasn’t accidental-it was the result of global cost optimization over the last 30 years. Companies moved production overseas to cut expenses, and regulatory systems allowed it. The trade-off was reliance on distant, sometimes unstable, suppliers.

Can we just make all drugs locally?

Technically, yes-but it’s not practical or affordable. Building a single GMP-certified API plant costs $200 million or more and takes 3-5 years. Labor costs in Australia or the U.S. are nearly five times higher than in China. Even if every country tried to reshore, it would take decades and cost trillions. The smarter move is multi-shoring: spreading production across multiple regions to reduce risk without sacrificing efficiency.

How do supply chain delays cause drug shortages?

Most modern drugs rely on multiple components from different countries. A pill might have an API from China, a coating from Germany, and packaging from Mexico. If any one link breaks-due to a port strike, export ban, or factory shutdown-the entire chain stops. Because companies use just-in-time inventory to save money, they don’t keep extra stock. So when one factory closes, shelves go empty within weeks.

Is nearshoring to Mexico really effective?

Yes, for many drugs. Shipping from Mexico to the U.S. takes 3-5 days instead of 30+ from Asia. Customs clearance is faster, and time zones align. While labor costs are 15-20% higher than in China, the total landed cost is often lower because of reduced shipping, warehousing, and delay risks. Companies like Teva and Mylan have already shifted production of antibiotics and blood pressure meds to Mexico with success.

What can patients do about drug shortages?

Talk to your pharmacist and doctor. Ask where your medication is made. If it’s from a single-source country, ask if there’s a therapeutically equivalent alternative made elsewhere. Keep a 30-day supply on hand if possible. Support policies that fund local production and drug stockpiles. And don’t assume shortages are temporary-they’re becoming structural. Awareness is the first step to change.

Are drug shortages getting worse?

Yes. In 2020, Australia recorded 67 drug shortages. By 2025, that number had risen to 124. The U.S. saw a 40% increase in critical drug shortages between 2022 and 2025. Climate events, trade wars, and geopolitical instability are making disruptions more frequent and longer-lasting. What used to be rare is now expected. The system is under strain-and it’s patients who pay the price.

November 17, 2025 AT 23:20 PM

why do we even bother making drugs here when china can do it for a penny

my insulin cost me 500 bucks last month and they told me its because the api came from shanghai and some port dude went on strike

like wtf is this a movie

November 18, 2025 AT 14:14 PM

yo i just got back from my pharmacy and they gave me a different brand of metformin - same pill, different box, same life-saving effect

turns out the chinese factory had a power hiccup so they switched to vietnam for a few months

honestly? i’m kinda glad

the new batch tastes less like chalk and the refill came in 10 days instead of 6 weeks

multi-shoring isn’t fancy jargon - it’s just common sense

we’ve been gambling with lives for too long

time to stop betting everything on one factory in one country

if your meds come from a single source, you’re not just taking pills - you’re playing russian roulette

November 19, 2025 AT 02:20 AM

this is all a deep state plot to control the population

the real reason they outsource to china is so they can poison us slowly with nano-toxins in the apis

watch the videos - the chinese labs are using AI to tweak drug formulas to make people dependent

and the FDA? totally in on it

they dont want you healthy - they want you buying pills forever

they shut down local plants so you HAVE to rely on the system

mark my words - this is bio-control 2.0

November 20, 2025 AT 00:46 AM

the real bottleneck isn’t geography - it’s GMP certification lag

building a compliant API facility takes 3–5 years because of regulatory friction, not capital

the EU and FDA have overlapping but non-aligned standards, so manufacturers are stuck in compliance purgatory

add to that the shortage of qualified validation engineers - we’re talking less than 2000 globally who know both ICH Q7 and 21 CFR Part 11

multi-shoring helps, but without harmonized regulatory pathways, we’re just moving deck chairs on the Titanic

we need a global API certification mutual recognition agreement - stat

November 20, 2025 AT 22:08 PM

in india we make most of the generic pills but even we depend on china for some raw chemicals

its not about blame its about survival

we all need each other

but yes - too much reliance is dangerous

November 22, 2025 AT 19:23 PM

The structural vulnerabilities exposed in global pharmaceutical supply chains represent a critical public health governance failure. The absence of a coordinated, multilateral regulatory framework for active pharmaceutical ingredient sourcing has resulted in systemic fragility. The reliance on just-in-time inventory models, while economically optimal in a static environment, is demonstrably untenable in the context of climate-induced logistical disruptions and geopolitical volatility. It is imperative that national health authorities prioritize the establishment of resilient, multi-sourced production ecosystems as non-negotiable components of health security infrastructure.

November 23, 2025 AT 00:13 AM

i keep thinking about that cancer patient in sydney waiting six weeks...

and i wonder - what if it was my mom?

what if the drug she needed wasn't just a pill, but the only thing standing between her and silence?

we talk about cost savings like they’re a victory, but every cent we saved on a metformin tablet was paid in sleepless nights by someone’s child

this isn’t economics - it’s ethics

we traded human dignity for efficiency and now we’re trying to patch it with ‘multi-shoring’ like it’s a bandage on a severed artery

maybe the real question isn’t how to fix the supply chain…

but whether we deserve to be healed by a system that treats medicine like a commodity

November 24, 2025 AT 06:50 AM

so now we gonna pay 3x for drugs just so we can have them faster

great

and who’s gonna pay for that? me?

my insurance already hikes my copay every year

and now i gotta pay for mexican labor too?

lol no thanks

china gets it done cheap and fast

if you want it faster pay up

or stop being a baby

November 25, 2025 AT 01:46 AM

why are we even talking about this

just make the drugs here

its not that hard

we have the tech

we have the people

we just dont want to pay for it

its all about greed

November 25, 2025 AT 21:22 PM

I appreciate how this article highlights the importance of global cooperation in healthcare. Many people forget that medicine doesn’t recognize borders. A patient in Australia, a pharmacist in Germany, and a factory worker in Vietnam are all part of the same human story. When we support local production alongside international partnerships, we’re not just ensuring access to drugs - we’re honoring the dignity of everyone involved in the process. Let’s build bridges, not walls.

November 26, 2025 AT 04:15 AM

This is textbook elite manipulation. The pharmaceutical-industrial complex has engineered this dependency to consolidate power. By outsourcing API production to authoritarian regimes, they ensure compliance through economic coercion. The 'multi-shoring' narrative is a distraction - it allows them to maintain control while appearing progressive. Real sovereignty would mean nationalizing critical drug production under public trust, not outsourcing to Poland and Mexico under corporate banners. The fact that you're still debating this proves how deeply the propaganda has taken root.

November 26, 2025 AT 15:51 PM

you think this is bad? wait till you find out the vaccines you got in 2021 were laced with microchips that sync to your phone via 5G and the same factories that made your blood pressure meds are also producing the chips that track your emotions

they’re not just making drugs - they’re making obedient citizens

i know this because my cousin’s neighbor’s dog got sick after a shipment from shanghai and now it barks in binary

and the FDA won’t tell you because they’re paid by the same people who own the ports and the satellites and the AI that predicts when you’ll need your next pill

wake up

they’re not letting you live - they’re letting you consume

November 27, 2025 AT 14:49 PM

just a heads up - the new mexican insulin plant i work at? we had a minor glitch last week. power surge. 2 hours downtime.

but because we had backup generators and the api was stored in poland, we didn’t miss a single order

it’s not perfect - but it works

i’ve seen the old way. this is better

November 28, 2025 AT 06:22 AM

Georgia nailed it. The real win isn’t just having multiple suppliers - it’s having redundancy in energy, logistics, and digital systems. We’re seeing companies now run parallel digital twins of their supply chains - one live, one simulated. If the real chain glitches, they reroute in the simulation before it even hits the warehouse. That’s not just resilience. That’s foresight.