When someone you love is using drugs, you can’t always be there to watch over them. But you can be the one who recognizes the warning signs before it’s too late. Overdoses don’t always look like what you see on TV. Sometimes, the person is just lying there, silent and still. Other times, they’re making strange gurgling noises, their skin is turning gray, and their breathing has slowed to almost nothing. If you don’t know what to look for, you might think they’re just passed out-or worse, that they’re fine. That’s why teaching your family how to spot an overdose isn’t just helpful-it’s life-saving.

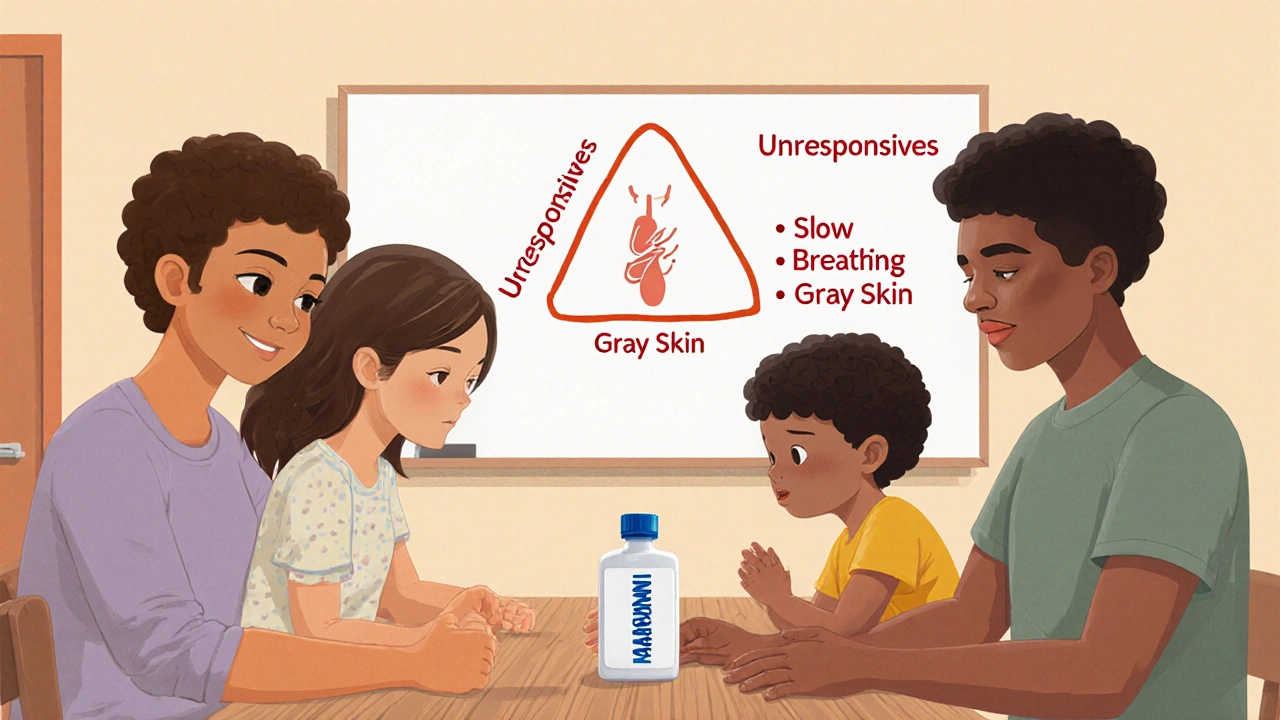

What an Overdose Actually Looks Like

Many people confuse being high with an overdose. But they’re not the same. Someone who’s high might be dizzy, giggly, or sleepy-but they’ll still respond if you shake them or shout their name. Someone having an overdose won’t wake up at all. Their body goes quiet. Their breathing slows or stops. Their lips and fingernails turn blue or gray. This is especially true with opioids like heroin, fentanyl, or prescription painkillers.

The three key signs to remember are the opioid triad: unresponsiveness, slow or stopped breathing, and bluish or grayish skin. If you see even two of these, it’s an overdose. Don’t wait. Don’t hope they’ll wake up. Act immediately.

For stimulants like cocaine or meth, the signs are different. The person might be sweating heavily, shaking, or having a seizure. Their heart could be racing, their body temperature soaring past 104°F. They might panic, scream, or collapse. These overdoses are just as deadly, even if they look more dramatic.

And here’s something most people don’t know: skin color changes don’t always look blue. On darker skin, the lips, gums, or nail beds may turn ashen gray or purple. If you’re not trained to look for that, you might miss it. That’s why training materials now include skin tone guides-because saving a life means seeing the signs no matter what someone looks like.

Why Family Members Are the First Responders

Most overdoses happen at home. According to the CDC, 78% of drug overdose deaths occur in private residences. That means the person who finds them isn’t a paramedic-it’s a parent, sibling, partner, or child. And in those first few minutes, your actions can make the difference between life and death.

Research shows that if someone gets naloxone (also called Narcan) within four minutes of stopping breathing, there’s a 98% chance of survival. But naloxone won’t help if no one knows how to use it-or worse, if no one realizes it’s an overdose at all.

One study found that families who were trained in overdose recognition were 40% more likely to save a life than those who weren’t. That’s not a small number. That’s hundreds of lives saved every day across the U.S. And it starts with you learning the signs-and then teaching the people around you.

How to Teach It: The Recognize-Respond-Revive Method

Don’t just hand someone a pamphlet and say, “Read this.” People forget. But if you practice, they remember.

The most effective method used by health departments nationwide is called Recognize-Respond-Revive. Here’s how to teach it:

- Recognize: Show them the signs. Use real photos or videos of actual overdose cases (from trusted sources like SAMHSA or Overdose Lifeline). Point out the difference between someone who’s just drunk and someone who’s overdosing. Practice asking: “Would you wake them up? Would you call 911?”

- Respond: Teach them what to do next. First, call emergency services. Then, if they have naloxone, give it. If they don’t, start rescue breathing. Don’t wait for EMS to arrive-every second counts.

- Revive: Practice using a training naloxone kit. These aren’t real drugs-they’re safe, reusable devices that click and spray just like the real thing. Let everyone in the family take turns. Have them practice on a mannequin. Do it in the kitchen, on the couch, anywhere. Make it normal.

Studies show that families who practice with these kits retain 89% of what they learn after three months. Those who just watch a video? Only 42% remember. Practice isn’t optional. It’s the core of the training.

Getting the Tools You Need

You don’t need to be a doctor to do this. You just need the right tools.

First, get naloxone. In 31 states, you can walk into a pharmacy and ask for Narcan without a prescription. In others, you’ll need to complete a short training-often free-at a local health clinic or community center. The cost? Around $35 for a two-dose kit. That’s less than a dinner out. It’s the cheapest insurance you’ll ever buy.

Second, get a training kit. Many harm reduction organizations give them away for free. The Overdose Lifeline, the Harm Reduction Coalition, and your local health department can help. These kits include a practice nasal spray, a mannequin, and sometimes even scenario cards that simulate real situations.

Third, use free resources. YouTube has dozens of real, no-fluff videos from trusted groups like SAMHSA and the CDC. Watch them together. Pause. Talk about what you see. Ask: “What would you do here?”

Overcoming the Emotional Barriers

Let’s be honest: talking about this is hard. Many families avoid it because they’re afraid. Afraid it’ll make things worse. Afraid they’ll “jinx” their loved one. Afraid they’ll have to face the reality that someone they love is in danger.

That fear is real. But here’s what the data says: 92% of families who went through training said their fear disappeared after they practiced. One father on Reddit wrote: “I thought I was being negative by learning this. Then my son overdosed. I gave him Narcan before the ambulance got there. He’s alive because I didn’t wait.”

Start small. Don’t make it a big speech. Say: “I found this thing online. It’s simple. Let’s watch it together.” Make it part of your routine-like checking smoke detectors. You don’t wait until the house is on fire to test them.

And if someone resists? Don’t push. Just leave the training kit on the counter. Leave the video link in a group chat. Let them come to it when they’re ready. The goal isn’t to force a conversation-it’s to make sure the tools are there when they’re needed.

What to Do If You See an Overdose

Here’s the exact step-by-step you need to memorize:

- Shout their name and rub your knuckles hard on their sternum (center of chest). If they don’t respond, it’s an overdose.

- Call 911 immediately. Say: “Someone is not breathing. I think it’s an overdose.”

- If you have naloxone, spray one dose into one nostril. Don’t wait for EMS. Don’t ask for permission. Just do it.

- If they’re not breathing, start rescue breathing: tilt the head back, pinch the nose, give one breath every five seconds.

- Stay with them. Even if they wake up, they can overdose again. Wait for EMS to arrive.

That’s it. No complicated steps. No medical degree needed. Just action.

What’s Changed in 2025

Overdose trends have shifted. Fentanyl is now in nearly 9 out of 10 illicit opioids. That means even a tiny amount can kill. That’s why newer training now includes fentanyl test strips-small paper strips you can use to check if drugs are laced. They cost less than a dollar each and can be carried in a wallet.

Also, polysubstance overdoses-where someone takes more than one drug at once-are now the norm, not the exception. That makes recognition even harder. But the core signs haven’t changed: no response, no breathing, blue-gray skin. Those are still your red flags.

And now, 100% of U.S. state health departments offer free family overdose training. You don’t have to search far. Just call your local health clinic or visit their website. Most have online sign-ups and in-person sessions every week.

It’s Not About Blame. It’s About Survival.

This isn’t about judging someone’s choices. It’s about keeping them alive long enough to get help. Addiction is a medical condition. Overdose is a medical emergency. And the most powerful tool we have isn’t a drug or a law-it’s a family who knows what to do.

Teaching your family how to recognize an overdose isn’t a one-time event. It’s a habit. Like knowing where the fire extinguisher is. Like checking the battery in the smoke alarm. You don’t do it because you expect disaster. You do it because you care enough to be ready.

And if you do-really do-it might just be the most important thing you ever do.

What are the main signs of an opioid overdose?

The three key signs are: unresponsiveness (can’t wake them up even with a sternum rub), slow or stopped breathing (fewer than one breath every five seconds), and bluish or grayish skin, especially on the lips and fingernails. These are called the opioid triad. If you see two of these, treat it as an overdose.

Can I give naloxone to someone who’s not overdosing?

Yes. Naloxone only works on opioids and has no effect if the person hasn’t taken them. It’s safe to use even if you’re unsure. Giving it to someone who isn’t overdosing won’t harm them. But not giving it to someone who is could kill them.

Do I need a prescription to get naloxone?

In 31 states, you can walk into a pharmacy and ask for Narcan without a prescription. In other states, you may need to complete a short, free training. Many community health centers give it away for free. Check with your local health department or harm reduction organization.

How do I recognize overdose signs on darker skin?

On darker skin, the blue or purple tint of cyanosis may not be visible. Instead, look for grayish, ashen, or pale skin on the lips, gums, nail beds, or inside the mouth. Training materials now include skin tone guides to help with this. Always check multiple areas, not just the face.

Is it safe to practice with a training naloxone kit?

Yes. Training kits use harmless devices that mimic the real spray-no drugs involved. They’re designed for practice and are completely safe to use on mannequins or even on yourself. Practicing builds confidence and muscle memory so you act quickly in a real emergency.

What should I do if the person wakes up after naloxone?

Even if they wake up, stay with them. Naloxone wears off after 30-90 minutes, but opioids can stay in the system longer. They could overdose again. Call 911 anyway. Medical professionals need to monitor them. Never assume they’re out of danger just because they’re awake.

November 26, 2025 AT 11:58 AM

Man, this is the kind of info that should be taught in high school. I learned all this after my cousin overdosed last year-thank god we had Narcan at home. The part about skin tone changes? Eye-opener. I never realized gray lips on darker skin could mean death. Everyone needs to see this.

November 27, 2025 AT 09:55 AM

Look, I get it-teach your family, save lives, yada yada. But let’s be real: most people won’t do this until it’s too late. We’re a nation of couch potatoes who’d rather scroll TikTok than learn how to save someone’s life. And don’t even get me started on the ‘it’s not my job’ crowd. If you’re not willing to practice with a training kit, you’re not ready to be a family member. Sorry, but that’s the truth. America’s addicted to denial-and now it’s killing us. 🇺🇸

November 28, 2025 AT 05:16 AM

Bro, this is gold. I’m from Nigeria and we don’t talk about this stuff much-but I shared this with my cousins who live in Chicago. One of them just got a Narcan kit last week after reading this. Seriously, the Recognize-Respond-Revive method? Perfect. I’ve been telling everyone: it’s not about judging, it’s about being ready. Like wearing a seatbelt. You don’t do it because you think you’ll crash-you do it because you care. And hey, if you’re scared to bring it up? Just leave the training kit on the counter. Let curiosity do the work. 🙌

November 28, 2025 AT 08:10 AM

This made me cry. 😭 My brother’s been sober for 18 months, but I still keep Narcan in my purse. I don’t want to wait until it’s too late. I showed my mom this article-she’s 72 and now she knows how to use the spray. She said, ‘If I can learn to use Zoom, I can learn to save a life.’ Love you, Mom. 💕

November 30, 2025 AT 00:59 AM

Man, I used to think this stuff was for ‘other people.’ Then my buddy OD’d last winter-thank god his roommate had Narcan. I didn’t even know what it was until then. Now I carry a kit in my backpack. I bought one for my sister too. It’s not morbid-it’s responsible. And practicing with the dummy? Weird at first, but now I do it while watching Netflix. Muscle memory, folks. It saves lives. 🤝

December 1, 2025 AT 04:43 AM

THIS IS A GOVERNMENT PSYOP. Naloxone is just a tool to keep addicts alive so they keep using-and the feds profit from the drug trade. Why don’t you ask why 90% of fentanyl comes from China? Why is the DEA letting it flood the streets? This ‘training’ is just a distraction. Let them die. It’s the only way the system resets. 🤡

December 2, 2025 AT 17:45 PM

I’m so tired of people acting like this is some revolutionary idea. We’ve had public overdose education since 2017. If your family doesn’t know how to respond, that’s not a system failure-it’s a personal failure. You had access to free training, free kits, YouTube videos, and yet you waited until someone almost died? Shame. 🙄

December 4, 2025 AT 09:18 AM

While the sentiment underlying this missive is undoubtedly well-intentioned, one must question the epistemological foundation upon which such interventions are predicated. The conflation of medical emergency with familial duty, while emotionally resonant, risks the commodification of human suffering under the guise of civic responsibility. One cannot moralize survival when structural inequities remain unaddressed. A Narcan kit is not a substitute for universal healthcare. Sincerely, a concerned academic.

December 5, 2025 AT 22:50 PM

Can we just agree that this is the most important thing you’ll ever do? Like, ever? Seriously. If you don’t teach your family how to recognize an overdose, you’re not just being negligent-you’re potentially complicit. And don’t say ‘I didn’t know’-you had this article. You had the links. You had the time. You had the resources. So don’t cry when it’s too late. 🙏

December 6, 2025 AT 01:43 AM

Ugh. Another ‘save a life’ guilt trip. I’ve got three kids and a job. I don’t have time to practice spraying fake Narcan on a mannequin while my toddler screams for cereal. If you’re gonna die from drugs, maybe you shouldn’t have done them in the first place. 🙄